MARCEL DUCHAMP MATERIALIZED PHILOSOPHY

Copyright © duchamp.co 2024

All Rights Reserved

This essay sets forth explanations of works of Art by Marcel Duchamp called “readymades”.

Philosophical concepts are the basis of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades. Although those concepts are generally understood by individuals with a background in philosophy, those concepts are frequently not understood by, and are often unknown to, many others who have an interest in Art. For those other individuals the following will hopefully provide an understanding of concepts that Marcel Duchamp illustrated with his readymades, and explain the key role that philosophy provides in decrypting Marcel Duchamp’s readymade works of Art.

In an effort to make the interpretations of Duchamp’s readymades that are provided in this essay clear, a number of preliminary matters are addressed in the following paragraphs.

Numerous quotations and explanations regarding various philosophical concepts appear below, to provide definitions and descriptions of the concepts illustrated by Marcel Duchamp. They are also provided to furnish information about: What contemporaries of Duchamp in the avant-garde world of Art have said about his readymades; and what philosophers and other highly creative individuals throughout history have said about the philosophical concepts that Duchamp materialized with his readymades.

It may be best to note at the outset why some of the following explanations and interpretations of readymades may be frowned upon by professional Art historians and philosophers. Art historians (as well as Art curators, critics, gallerists, and collectors) may be disinclined to accept some of the following explanations of readymades on account of those explanations not being a part of their generally accepted, professional and historical, narratives. Philosophers on the other hand, such as those who have gone deep into the epistemological weeds (regarding the nature of knowledge, seeing, and thinking), who are likely to be familiar with the philosophical works of philosophers such as Fred Dretske, Hilary Putnam, Jerry Fodor, Gilbert Ryle, Gottlob Frege and Saul Kripke, may object to explanations or to the application of philosophical concepts that are set forth below, because from their learned perspective they may appear to be pedestrian or superficial.

Be that as it may, the following explanations and interpretations are provided in hopes that you will find that they do in fact explain and correctly interpret some of the most creative works of Art of the twentieth century—the readymades of Marcel Duchamp.

– – ⸪ – –

Marcel Duchamp’s readymades are works of conceptual Art, that materialize philosophical concepts. They were made to be, and they are in fact, very different from traditional pictures and sculptures that have been made throughout history. Traditional works of Art have been created to provide, and they do provide, their observers with a visual image, so that they see a picture or sculpture that looks more or less like objects, people and/or places that the artist has seen and/or imagined. Traditional Art of that kind has been referred to by Marcel Duchamp as “retinal art”.

Many of Duchamp’s readymades (as well as his painting entitled Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, which is described below) were primarily created to do, and in fact they do, something different from “retinal art”. Readymades were created to, and they can, and do in fact, communicate and materialize (that is, they embody and instantiate) one or more philosophical concepts regarding how we think about the things that we see; that is, how we identify, categorize, understand and thereby think about the physical objects that we see. In philosophy, those concepts are often referred to as “seeing-as”. In other words, Duchamp created readymades to illustrate and communicate in material form the fact that people have previously existing (already made) concepts that they have learned and use to identify, categorize and understand (that is, how people think about) the objects that they see. And the fact that Marcel Duchamp in fact did so is just one of the reasons why he has made significant contributions to modern art and is widely regarded to be one of the most inventive artists of the twentieth century.

It should be noted here that this article discusses only some of the readymades created by Marcel Duchamp, to explain some of the ideas that he addressed, illustrated and conveyed with readymades. There are numerous works of Art that were created by Marcel Duchamp, and philosophical concepts that he addressed with his Art, that are not discussed below, including other readymades, numerous paintings, drawings and constructions; as well as two monumental artistic creations, one commonly called The Large Glass on which Duchamp worked for eight years from 1925 until 1923, and the other called Étant donnés on which he worked for twenty years from 1946 until 1966 (both of which are presently located at the Philadelphia Museum of Art). But even without addressing those other works, the readymades discussed below, taken by themselves, serve to establish Marcel Duchamp as a leading artist of the twentieth century, who among other things made cerebral ideational Art an accepted Art form, and who has for more than a century had, and who continues to have, an enormous influence on the world of Fine Art.

There is a topic in philosophy which provides a basis for various philosophical concepts that are addressed by Duchamp with his readymades. The topic is “seeing-as”. It includes two basic concepts regarding the ways in which people perceive what they see. One of those ways we will generally call “subjective”, and the other way we will generally call “objective”. A physical thing is seen in what we call a “subjective” manner, when a person sees an object as being a member of a particular class or category of things that the person has learned (and usually designated with a name) as being a particular type of thing. But that is not done when something is seen in what we call an “objective” manner. When a person sees something in an “objective” manner, it is seen as being one, single, as-yet unidentified, unfamiliar, unclassified, uncategorized, un-named type of object that has no particular use, that exists in-and-of-itself; and that object is, therefore, not seen as being a particular type of thing. Those two concepts, of seeing something subjectively and of seeing something objectively, are just two among numerous other philosophical concepts that Marcel Duchamp illustrated and materialized with his readymades. It is important to note that although for many individuals those concepts are strange or unknown, for many philosophers, artists, and countless others who have looked deep into the basic nature of how we perceive, think and communicate about what exists in our physical world, those concepts have been of great interest, and have been discussed and written about at great length, throughout history. For example, Aldous Huxley, in his book Heaven and Hell (Chatto & Windus, London, 1956,) said:

. . . [O]ur perceptions of the external world are habitually clouded by the verbal notions in terms of which we do our thinking. . . . At the antipodes [that is, in the non-verbal part] of the mind, we are more or less completely free of language, outside the system of conceptual thought. Consequently our [non-verbal] perception of visionary objects possesses all the freshness, all the naked intensity, of experiences which have never been verbalized, never assimilated to lifeless abstractions. . . . [and] the facts of external nature, are independent of man, both individually and collectively, and exist in their own right. . . . Everything [seen in that non-verbal manner] is novel and amazing. Almost never does the visionary see anything that reminds him of his own past. He is not remembering scenes, persons, or objects, and he is not inventing them; he is looking on at a new creation. [Inserts in brackets added, Ed.]

In an effort to avoid misinterpretations that some individuals may have regarding concepts referred to in this essay, the following two matters should be addressed. First, regardless of whether some thing (that is, some physical object) is seen subjectively or objectively, in both cases, how it is seen only relates to, and only affects, the perception and/or conception that exists in the mind of the person who sees the thing; because as a matter of fact, the way a person sees an object and what the person thinks about it does not materially affect or change the essential, physical nature of the thing that is seen. In other words, there is both what a person may subjectively or objectively see and/or think that the thing is; and, at the same time, there is also, in the three dimensional world that exists outside of that person’s mind, what the thing physically, actually is. And what it physically, actually is, is neither established nor affected whatsoever by what someone thinks about it, sees-it-as, or thinks that it is. So whatever you see-some-thing-as (and regardless of whether you see it in the manner we call “objective” or “subjective”), that does not change, and that in no way affects, what the thing essentially, actually, and in fact is in the physical world—it just changes what you think about the thing, what you think that it is and what you see-it-as. The second point to be addressed is that for some individuals it is necessary to make clear that the concepts regarding seeing-as that are addressed in this essay are based on a world-view that the objective, physical world outside of a person’s mind does in fact exist. Accordingly the belief that some nihilists, solipsists and others have that nothing exists, or that nothing can be known, or that nothing in-and-of-itself exists outside of the mind, are therefore neither discussed further nor deemed relevant in this essay. Incidentally, in an effort to not unduly disturb or unnecessarily alienate some relativists, social constructionists and postmodernists, it will hopefully suffice to say and confirm here that some aspects regarding esthetic judgments are mental constructs, fictions of the imagination; such that one’s personal judgements and opinions regarding the merit and beauty of a work of Art can be said to be, and are for that person, “in the eye of the beholder”.

It also bears mentioning that notwithstanding the fact that for over one hundred years Marcel Duchamp has been widely regarded as one of the leading and most celebrated artists of the twentieth century, both he and his works of Art have suffered from what may be called the “Einstein Syndrome”. That is, as is the case with Albert Einstein and the scientific theories that Einstein created, Marcel Duchamp and the body of work called readymades that Duchamp created, are famous throughout the world, have for over a century been considered by countless learned individuals to be important and ingenious, have been the subject of innumerable publications and discussions, have been studied, illustrated and exhibited in leading universities and museum around the world: and despite all that, very few individuals, museums or any other organizations have understood and explained why that is so.

It is, therefore, relevant to address how Art historians, critics, collectors, and other Art afficionados have often interpreted (and frequently, superficially and/or erroneously interpreted) Marcel Duchamp and his readymades; that is, what they see-them-as. They have often said that the readymades of Marcel Duchamp “Raise philosophical questions concerning the traditional definition of Art and the role of the artist”. Those questions, however, merely address the age-old, ultimately and definitively unanswerable (but nonetheless interesting) questions regarding: (1) what qualities something must have to make it a work of Art (that is, a work of Art that is more precisely called “Fine Art”); and (2) what qualities a person must demonstrate (such as outstanding skill) to be considered to be an artist (that is, someone who has produced “Fine Art”). Some have said that exhibiting in art galleries or museums readymades that are in large part ordinary objects (such as those that are found or purchased,) proves that it is merely the “context” (that is, how and/or where something is exhibited), rather than the content (that is, what is outstanding about the object and the skill of the artist that made it) that determines what, and whether something, is a work of Fine Art. Some have said that Duchamp was iconoclastic— merely rebelling against the standards of traditional Fine Art. A few have entirely dismissed readymades, stating that they are not works of Fine Art. And some have said that Duchamp was just being whimsical, that he was merely joking; or merely making fun of the institution of Art itself (the so called “Art world”). However, although such explanations and interpretations are sometimes somewhat appropriate and relevant with respect to some of Duchamp’s readymades, at best they represent a partial view, a superficial, limited explanation and interpretation, of the genius of Duchamp and his readymades. And that is so because as described in detail below, what Duchamp expressed, illustrated and materialized with his readymades (as well with some of his other works of Art) was how and what we think about absolutely every thing that we see; that is, how we typically conceptualize, identify, classify and/or categorize all of the objects that we see, and what we think that they are—whereas the commonly expressed, rather superficial interpretations of readymades referred to above in this paragraph at best merely relate to how and what we sometimes identify, classify and think about only two things: Art and artists. What follows describes how and why those commonly expressed interpretations fail to recognize and appreciate the most important and creative aspects of readymades, by being much too narrow, superficial interpretations of the artistic achievements of Marcel Duchamp and his body of work called “readymades”.

– – ⸪ – –

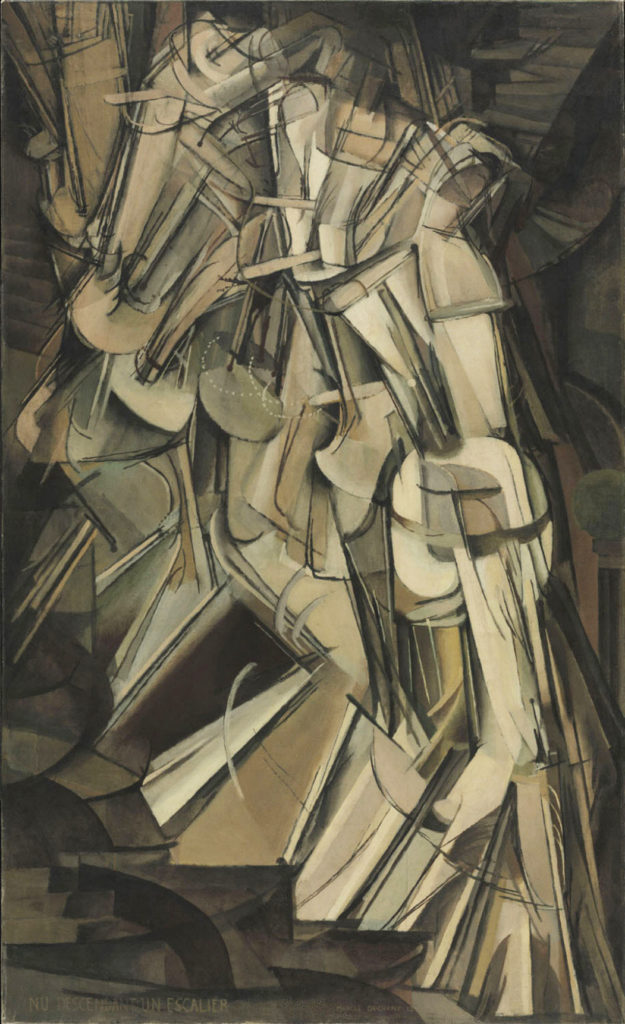

One of the first works of Conceptual Art made by Marcel Duchamp illustrates what was then a well-known philosophical concept among avant-garde Artists in France. It is Duchamp’s famous 1912 painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (French: Nu descendant un escalier n° 2,) a photograph of which appears below.

The philosophical concept that Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 illustrates, is how people think about a moving object as if it occupies successive fixed locations (stopping points) along its path as it moves; when in fact there are no such stoppages. People commonly do in fact have such readymade concept of stoppages when they think about an object in motion. For example, people think of an arrow which is shot at a target as if at some time it must be located at some point that is half way (or at some other fraction of the way) to the target. But in fact such hypothetical fixed points along the trajectory of a moving object are all merely mental constructs, fictions of human imagination, because the arrow is in fact never at rest; it is always in motion along its path to its destination. “Half way” in the example above is merely an idea, a mental construct, a concept. And the mental concept that people have of such hypothetical stoppages of an object in motion is the concept Duchamp illustrated with Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.

About ten years before Duchamp created Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, the readymade concept that people have when they think of objects in motion as if they have stoppages along their path, was brilliantly addressed in great detail in a well-known 1903 essay, first published in French as Introduction à la Métaphysique (an English translation of which is An Introduction to Metaphysics), written by Duchamp’s contemporary, the celebrated French philosopher Henri Bergson. During the decade from the publication of An Introduction to Metaphysics to the creation of Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, Henri Bergson and Marcel Duchamp were both widely known celebrities in the avant-garde world of the Arts in France. Duchamp was certainly aware of the concept of readymades described in Bergson’s book when he created Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. The expression “tout faits” (the English translation of which is in fact “readymade”) appears in Bergson’s book nine times, and “stoppages” are referred to in the book twelve times; in each case with respect to the philosophical concept of seeing-as that is referred to above. Note that the English translation by T. E. Hulme of the book An Introduction to Metaphysics, (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912,) which was authorized and revised by Henri Bergson, does in fact translate “tout-faits” as “readymade”.

The following quotation, from the Hulme translation of An Introduction to Metaphysics regarding “readymade concepts” and “stoppages” is pertinent with respect to Duchamp’s philosophical basis and motivation for his creation of Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.

Consider, for example, the variability which is nearest to homogeneity, that of movement in space. Along the whole of this movement we can imagine possible stoppages; these are what we call the positions of the moving body, or the points by which it passes. But with these positions, even with an infinite number of them, we shall never make movement. They are not parts of the movement, they are so many snapshots of it; they are, one might say, only supposed stopping-places. The moving body is never really in any of the points; the most we can say is that it passes through them. But passage, which is movement, has nothing in common with stoppage, which is immobility. A movement cannot be superposed on an immobility, or it would then coincide with it, which would be a contradiction. The points are not in the movement, as parts, nor even beneath it, as positions occupied by the moving body. They are simply projected by us under the movement, as so many places where a moving body, which by hypothesis does not stop, would be if it were to stop. They are not, therefore, properly speaking, positions, but “suppositions,” aspects, or points of view of the mind. [Hulme translation of An Introduction to Metaphysics (supra), at pages 48 – 49.]

– – ⸪ – –

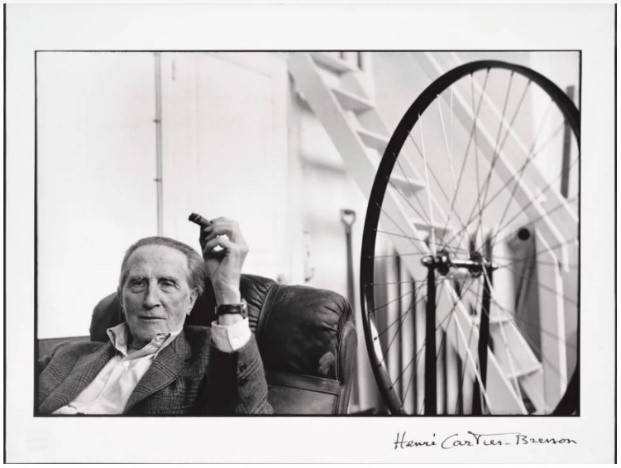

One of Duchamp’s first readymades is his 1913 creation known as “Bicycle Wheel” which is an assemblage composed of a bicycle wheel attached to the top of a four legged stool in a manner that enables the wheel to be spun. A photograph of the original of Bicycle Wheel located in Duchamp’s studio appears in the photograph below.

In the light of Duchamp’s interest in concepts related to “stoppages” and to the “flux” of motion which he evidenced by his creation the preceding year (in 1912) of Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2; it follows that he would have created Bicycle Wheel, having spokes that appear to occupy fixed locations at stopping points when the wheel is at rest, but that disappear into the “flux” in which they occupy no stopping points when he spins the wheel and they are in motion. Duchamp thereby materialized the same concept that he represented in Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. With respect to which it is interesting to note the 1952 photograph below of Marcel Duchamp with both a bicycle wheel and a staircase prominently displayed, by the renowned (and obviously insightful) French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson.

In the following year, 1914, Marcel Duchamp made a readymade entitled 3 Standard Stoppages, a photograph of which appears below. It consists of a wooden box that contains the following items. Three threads that would be one meter long if stretched straight, each of which was dropped from a height of one meter, curved as it fell, and when it landed was glued to a canvas strip that was then mounted onto a glass panel. Also enclosed are three slats of wood, each of which had one edge cut with curves to match the shape that one of the threads made when it landed.

With his creation of 3 Standard Stoppages, Duchamp illustrated and materialized examples of fixed locations (“stoppages”) of a falling string, that people think that it occupies (that is, “see-it-as” occupying) along the trajectory of its motion. We note, however, that some individuals have said that Duchamp created 3 Standard Stoppages to make tools with which “standardized” (although curved) nonlinear measurements of one meter can be made; thereby rejecting the common conception that a measurement of one meter must be “seen-as” (that is thought of as) being located along a straight line. In either case, with 3 Standard Stoppages Duchamp appears to have addressed the concept of “seeing-as”. And in any event, it would strain credulity for one to believe that with 3 Standard Stoppages Duchamp did not intend to address or that he was unaware of the references to the “readymade” concepts of “stoppages” described by Bergson in An Introduction to Metaphysics.

– – ⸪ – –

Duchamp made a significant number of readymades that are works of conceptual Fine Art to illustrate and instantiate (that is, to materialize) one or more concepts regarding “seeing-as” (often concepts other than “stoppages”) that people learn, have and use, to identify, categorize, understand and think about the objects that they see—that is, to determine what they “see things as”.

A Duchamp readymade that has often been referred to by Art historians and other Art professionals as a major landmark in 20th century Art, (which, as described below, illustrates and embodies the philosophical concept “seeing-as,”) is Marcel Duchamp’s readymade that consists of a (so-called) “urinal”, signed “R. Mutt 1917”, which is commonly referred to as Fountain. A photograph of Fountain taken by Duchamp’s contemporary, the famous photographer Alfred Stieglitz, appears below. The photograph is of the original of Fountain, which was lost; replicas of the original Fountain now appear in museums and private collections.

Duchamp’s Fountain illustrates the concept seeing-as by evidencing that a person who sees an object as being a particular type of thing (that is, sees it “subjectively” as described above, as a member of a particular category or class of things that is used for a particular purpose), does so only if that person had previously learned what an object with the same or similar physical characteristics as that object looks like and is used for. And on what may be a deeper level, Fountain also illustrates that if the person had not previously categorized or classified the object and learned what that form of object is used for (if he saw it “objectively” as described above), that person would not categorize, classify or see it as being anything in particular at all; not until that person thereafter invented or learned some use for that type of object.

An observer of Fountain, therefore, initially sees it as (that is, conceptualizes and categorizes it as) being a urinal only if that observer had previously acquired the concept of a “urinal” from having at some time in the past seen and used, or otherwise come to understand what a urinal looks like and is used for. That is so because if an observer of Duchamp’s Fountain had not previously seen and used, or otherwise learned what a urinal looks like and is used for, that observer would see Duchamp’s so-called “urinal” as some uncategorized object with an unknown use; not as a urinal. And that is the philosophical concept of seeing-as that Duchamp intended to, and did in fact, illustrate and materialize with his readymade Fountain.

Duchamp’s readymades are important works of Art because they represent and illustrate in material form, mental concepts regarding consciousness and knowledge—concepts about what we think about, and how we categorize and identify, the objects that we see. That is, how we classify what we think things are; what we see-them-as. And that, among other reasons, is why Marcel Duchamp is a conceptual Artist; and was in the twentieth century, and is now, a leading figure of in the Art world.

Marcel Duchamp’s intent to illustrate and materialize the concept seeing-as with Fountain is clearly stated in the Dada Art journal The Blind Man, Volume 2, of May, 1917; which was organized and published by Marcel Duchamp, with two of his well-known friends in the avant-garde world of Art, the writer and art critic Henri-Pierre Roché, and the publisher of The Blind Man, the artist Beatrice Wood. The article in The Blind Man entitled “The Richard Mutt Case” – “Buddha of the Bathroom” written by Duchamp’s friend, the writer, editor and translator of French literature, Louise Norton, states that when Marcel Duchamp created Fountain:

He took an ordinary Article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object. [Emphasis added, Ed.]

With respect to the fact that Fountain was rejected by The Society of Independent Artists and therefore not exhibited at its 1917 “First Annual Exhibition” Louise Norton states in her above referenced article “Buddha of the Bathroom”:

When the jurors of The Society of Independent Artists fairly rushed to remove the bit of sculpture called Fountain sent in by Richard Mutt, because the object was irrevocably associated [with prior conceptions] in their atavistic minds with a certain natural function of a secretive sort. [The definition of “atavistic” is having prior conception; and in the foregoing quotation Louise Norton is therefore explaining that the jurors rejected Fountain because they “saw-it-as” a urinal, Ed.]

The fact that Ms. Norton’s article refers to Fountain as “Buddha of the Bathroom” is explained by the lines of her article in which she states: “Yet to any ‘innocent’ eye how pleasant is its chaste simplicity of lie and color! Someone said, ‘Like a lovely Buddha’. . . .” Whether Louise Norton did or did not actually hear someone say that, by saying so she nonetheless clearly explained that the title of her article was based on the fact that the outline of Fountain (in particular the main cavity of Fountain) if observed by an “innocent” eye could see-it-as the shape of the sitting Buddha; and that was just another way for her to illustrate how Duchamp illustrated and addressed seeing-as with his readymade Fountain.

Louise Norton in “Buddha of the Bathroom” also explains the concept of seeing-as that was materialized by Fountain, by stating the example that: “. . . . although a man marry he can never be only a husband. Besides being a money making device . . . to his employees he is nothing but their ‘Boss,’ to his children only their ‘Father,’ and to himself certainly something more complex.”

With respect to the objection that some have to classifying Fountain as a work of Art that was made by Marcel Duchamp, in her article referred to above Louise Norton states:

To those who say that Mr. Mutt’s exhibit may be Art, but is it the Art of Mr. Mutt since a plumber made it? I reply simply that the Fountain was not made by a plumber but by the force of an imagination . . . .

Louise Norton’s explanations of Duchamp’s readymade Fountain contained in The Blind Man may well be the basis for the opinions expressed by some Art historians and other Art professionals that a readymade conveys an “idea”. But although that opinion is true; it is noteworthy and more than a bit disappointing, that just about none of them ever say or explain anything about what any of those ideas are or might be. It is of course customary for it to be said (including by Art experts) that each observer interprets a work of Art based on that person’s own standards and esthetic preferences. That is, of course, generally true. But just about none of the individuals who have expressed any opinions or interpretations regarding Duchamps readymades (regardless of their knowledge of Art, or their standards and esthetic preferences) have provided any evidence that they are aware that Duchamp intended to and did in fact illustrate and materialize philosophical concepts with his readymades (and not merely raise questions regarding what makes something a work of Fine Art and someone an Artist). As a result, Duchamp and his readymades, notwithstanding their world-wide fame, have to date generally been misunderstood, and suffered from the “Einstein Syndrome” referred to above.

For the benefit of any individuals who may still find the concept of “seeing-as” elusive or confusing, prior to addressing below several of the other philosophical concepts that Marcel Duchamp illustrated and materialized with his readymades, the following quotations of just a few of the many philosophers, and luminaries in other fields, who have addressed the concept “seeing-as” are presented to further clarify that concept.

“What a man sees depends both upon what he looks at and also upon what his previous visual-conceptual experience has taught him to see.”

Thomas Kuhn, (1922 — 1996)

“I look at a…stove…. I am comparing this experience with previous experiences. When I say to myself…stove… l am making a little theory to account for the look of it.”

Charles Sanders Peirce (1839 — 1914)

“We must interpret; we must find meaning in things, otherwise we should be quite unable to think about them. We must resolve life….into images, meanings, concepts….”

Carl Gustav Jung (1875 – 1961)

“All things are strange. One can always sense the strangeness of a thing once it ceases to play any part; when we do not try to find something resembling it and we concentrate on its basic stuff, its intrinsicality.”

Paul Valéry (1871 –1945)

“I believe that nothing can be more abstract, more unreal, than what we actually see. We know that all that we can see of the objective world, as human beings, never really exists as we see and understand it. Matter exists, of course, but has no intrinsic meaning of its own, such as the meanings that we attach to it. Only we can know that a cup is a cup, that a tree is a tree.”

Georgio Morandi (1890 – 1964)

“Concepts…have the disadvantage of being in reality symbols substituted for the object they symbolize…. We inquire up to what point the object we seek to know is this or that, to what known class it belongs, and what kind of action, bearing, or attitude it should suggest to us. These different possible actions and attitudes are so many conceptual directions of our thought, determined once for all; it remains only to follow them: in that precisely consists the application of concepts to things. To try to fit a concept on an object is simply to ask what we can do with the object, and what it can do for us…. This is why it happens that our knowledge of the same object may face several successive directions and may be taken from various points of view.”

Henri Bergson (1859 – 1941), in An Introduction to Metaphysics, supra.

With respect to individuals unfamiliar with the concept of seeing-as, it may also be explained, illustrated and clarified by the following example. Imagine that a highly intelligent adult native who had always lived in the wilderness, without contact of any sort with anyone or anything outside of his isolated primitive world, one day finds the white porcelain object (Duchamp’s Fountain) that is shown in the image above. What would he think that the object was? What would he think that it should be used for? He might see it as being a rare, beautiful object, in which to display precious ornaments. He might see it as being a mysterious, sacred object, to be worshipped by the members of his tribe. It is more likely that he would see it in one of those ways or as something else, but not as a urinal. The point of the foregoing example being that the object shown in the image above is not necessarily seen as a urinal; because in fact, essentially it is not a urinal. It is merely whatever a person learns to use, name, identify and classify that object as. And the use, name, identity and classification that a person creates for or learns about an object is what that person sees that object to be. In other words; that is what the person sees the object as. That is the concept seeing-as that Marcel Duchamp addressed, illustrated and materialized with Fountain.

– – ⸪ – –

Duchamp was not only interested in the concept of seeing-as. He was also aware of, attracted to, and interested in living in accordance with, an objective world-view based on “not-seeing-as”; that is, a world view that we sometimes refer to as “Non-Conceptual-Perception”. He indicated his interest in the philosophical concept of “not-seeing-as” in a note in the 1934 boxed collection that he created of 94 documents, entitled The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors Even, which is called The Green Box, in which Duchamp stated: “To lose the possibility of recognizing 2 similar objects—2 colors, 2 laces, 2 hats, 2 forms whatsoever. To arrive at the Impossibility of sufficient visual memory, to transfer from one like object to another the memory imprint.”

With respect to the foregoing statement by Duchamp, the following quotation from Heaven and Hell by Aldous Huxley addresses the same idea.

[O]ur perceptions of the external world are habitually clouded by the verbal notions in terms of which we do our thinking. We are forever attempting to convert things into signs for the more intelligible abstractions of our own invention. But in doing so, we rob these things of a great deal of their native thinghood.

At the antipodes [that is, the non-verbal, non-conceptual aspects] of the mind, we are more or less completely free of language, outside the system of conceptual thought. Consequently our perception of visionary objects possesses all the freshness, all the naked intensity, of experiences which have never been verbalized, never assimilated to lifeless abstractions…. unsophisticated by language or the scientific, philosophical, and utilitarian notions, by means of which we ordinarily re-create the given world…. The self-luminous objects which we see in the mind’s antipodes possess a meaning,… identical with being; for at the mind’s antipodes, objects do not stand for anything but themselves…. and exist in their own right. And their meaning consists precisely in this, that they are intensely themselves…. Everything is novel and amazing. Almost never does the visionary see anything that reminds him of his own past. He is not remembering scenes, persons or objects, and he is not inventing them; he is looking on at a new creation.

Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor, who was married to Marcel Duchamp from 1927 to 1928, in her book A Marriage in Check: The Heart of the Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelor, Even (trans. Paul Edwards; Dijon: les presses du réel, 2007), quotes Duchamp as having given her advice to: “Find yourself, the pure self, like a child newborn…. You have to try to see everything as if for the first time, all the time . . . .”

The relationship between Marcel Duchamp’s readymades and “Not-Seeing-As” was well stated in the article by the French writer, linguist and Art historian, Mark Décimo entitled “A Sentimental Conversation: Marcel Duchamp and Lydie Sarazin-Levassor”, in the book by Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor, A Marriage in Check, The Heart of the Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelor, Even, les presses du reel, 2007, Paul Edwards, trans., as follows:

A readymade induces the viewer to discover the world anew. Instead of letting habit determine what is seen—what is no longer seen—the object must once more become an object of experience. And so, with nostalgia for the pre-verbal state that characterises the infans (he who does not speak), Marcel Duchamp would appear to have been able to re-experience the sensations procured in infancy by inert objects, living things, words and situations that were all still unfixed. Readymades recreate that ineffable moment in life, the pre-linguistic stage, during which the child is at the mercy of the other and of the world, and must develop his cognitive powers when confronted with animate and inanimate objects, all of them exotic, all of them just hanging suspended in the air. Around 1917/1918, Duchamp took a urinal, a hat rack, a snow shovel and bits of rubber and hung them up from the ceiling of his New York studio, making them strange again. Once put into such an arrangement, the objects conspired to recreate a state that exists before naming, when nothing in the world is completely laid down nor completely finalised, when nothing is built, and when everything has yet to be experienced. Duchamp’s quest is to search for these first sensations, which means always beginning again. Everything has to be thought through again, at every moment.

Accordingly, Marcel Duchamp’s readymades not only illustrate various concepts of “seeing-as,” they also illustrate the philosophical concept that things in and of themselves have no inherent meaning—that without ready-made (already made) concepts we do not identify, categorized or think about an object as a particular type of thing. Essentially, that is “not-seeing-as,” or what we have called “Non-Conceptual-Perception;” which in Eastern philosophy (as is described in more detail below) is the absence of “Duality” that Zen Buddhists contend is a delusion.

– – ⸪ – –

A readymade that illustrates Duchamp seeing an object in a new light; of not seeing it as what it was originally made to be used for, and not as what it is typically seen as, is Duchamp’s 1957 readymade called The Locking Spoon. It consists of a (so-called) “spoon” that Duchamp affixed to the door of his Manhattan apartment in the late 1950s; a photograph of which appears below. With respect to this readymade it may be said (as his Artist-friend Louise Norton stated above with respect to Duchamp’s Fountain): Duchamp “created a new thought for that object.”

– – ⸪ – –

A famous Duchamp readymade that illustrates an aspect of the philosophical concept “seeing-as” that is somewhat different than those described above, is his work of conceptual Art (which is referred to in the quotation by Mark Décimo above) known as In Advance of the Broken Arm. It consists of a snow shovel that Duchamp purchased and hung from the ceiling of his studio, on the handle of which is written “from Marcel Duchamp 1915”. A photograph representing the original in Duchamp’s studio appears below on the left, and a 1964 replica displayed in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City appears on the right.

The ready-made philosophical concept of seeing-as that Duchamp illustrated with his snow shovel, is that an observer of an object sees-it-as, identifies and categorizes it, as a result of what the observer knows (that is, what the observer has learned) can be done with it, or what it can do to the observer. That philosophical concept, which we may call “Functional-Seeing-As”, has been addressed by many philosophers, including the following.

Henri Bergson in An Introduction to Metaphysics (supra,) stated:

To know a reality, in the usual sense of the word “know,” is to take ready-made concepts. . . . [I]n that precisely consists the application of concepts to things. To try to fit a concept on an object is simply to ask what we can do with the object and what it can do for us.

Charles S. Peirce, in his Article How to Make Our Ideas Clear, in the issue of Popular Science Monthly of January 1903, stated:

[T]he rule for attaining clearness of apprehension [of an object] is as follows: consider what effects…we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of out conception of the object.

William James, in his 1907 book Pragmatism (a New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking), Lecture II: What Pragmatism Means, stated:

A glance at the history of the idea [of pragmatism] will show you still better what pragmatism means…. It was first introduced by Mr. Charles Peirce in 1878…. Mr. Peirce…stated that…[t]o attain perfect clearness in our thoughts of an object, then, we need only consider what conceivable effects of a practical kind the object may involve – what sensations we are to expect from it, and what reactions we much prepare. Our conception of these effects, whether immediate or remote, is then for us the whole of our conception of the object. . . .

In the light of the philosophical concept regarding seeing-as described in the foregoing three quotations, it is apparent how philosophically aware and appropriate it was for Duchamp’s to give his readymade snow shovel the name “In Advance of The Broken Arm”.

– – ⸪ – –

A synthesis of sorts, of the concepts “not seeing as” and “Functional Seeing As” that are referred to above, is illustrated and materialized by Duchamp’s 1916 readymade shown below called With Hidden Noise; as one does not see it as a whole as being anything in particular or as serving any apparent function. The fact that when shaken it makes a sound from some hidden thing moving in its interior, and that the writing on the top plate when taken as a whole has no apparent meaning is obviously intentional and perfectly appropriate for an object which overall one sees as nothing in particular, serves no apparent purpose, and overall has no discernable meaning.

– – ⸪ – –

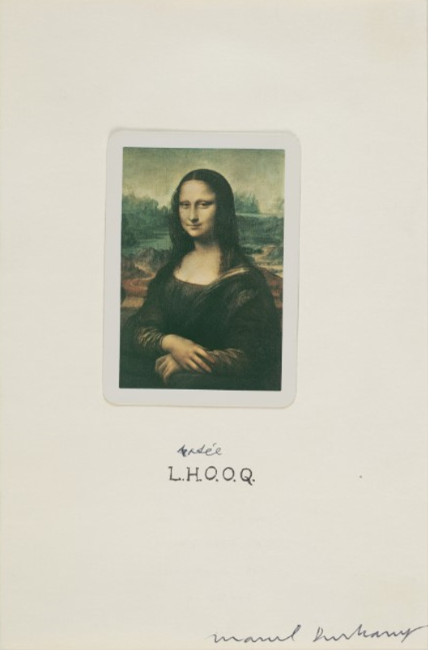

Several aspects of the philosophical concept “seeing-as” were illustrated and materialized by Duchamp with his well-known readymade of 1919 shown below, which consists of a postcard reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s painting Mona Lisa, on which Duchamp drew a moustache and a goatee in pencil, and which bears the title L.H.O.O.Q.

With his readymade L.H.O.O.Q. Duchamp illustrated the concept of androgyny, which is the state of a person (an androgyn) being seen as (that is, appearing to be) neither distinctively feminine nor masculine, or a combination of both. On a deeper level, Duchamp also illustrated the concept of “agenderism” (by which we mean seeing as being without gender). Duchamp did so by adding what are typically seen as, but are not necessarily, male features to the subject of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. The person depicted in the original of the painting who is commonly seen as an enigmatic woman, was thereby transformed by Duchamp into an androgyn. And by doing so Duchamp illustrated agenderism by causing the duality and classification of a person based essentially on gender to be eliminated; and thereby materializing the underlying and fundamental fact that man and woman are, essentially, the same—essentially they should just be seen-as human beings.

For clarity we note that the prefix “a” in “agenderism” (which prefix is called an “alpha privative”) indicates absence or negation; and, therefore, we use the word “agenderism” to mean the state of one being “without” gender. We also note that with L.H.O.O.Q Duchamp illustrated and materialized concepts of androgyny and gender which solely pertain to one’s subjective persona, not to one’s objective, inherent, immutable biological sex.

Duchamp took his materialization of concepts of seeing-as several levels deep by creating various versions of his readymade L.H.O.O.Q. During the period from 1935 until about 1941 Duchamp made reproductions of L.H.O.O.Q., and enclosed one in each of various editions that he made of his creation called The Box in a Valise; a mixed media assemblage consisting of a box that contains numerous reproductions of Duchamp’s works of Art. A photograph of one such box appears below. Note that when a person familiar with the art of Duchamp sees the reproduction of L.H.O.O.Q. in this boxed collection it is essentially seen-as a reproduction of a readymade by Duchamp, not as a da Vinci.

Duchamp went deeper regarding seeing-as with L.H.O.O.Q. when in 1965 he created the readymade called L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved, a photograph of which is shown below. It consists of the cover of a dinner invitation on which Duchamp mounted a color reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in its original form (without Duchamp’s mustache or goatee), below which is written “rasée” (which in French means “shaved”), and below that appears Duchamp’s signature. Note that when a person familiar with the art of Duchamp sees L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved, one is inclined to see-it as being an altered version of Duchamp’s readymade L.H.O.O.Q. without the whiskers.

Incidentally, it is interesting to note that an observer of the original of L.H.O.O.Q. (one who was familiar with the painting Mona Lisa) would be inclined to see L.H.O.O.Q. as an altered version of a work of art by Leonardo da Vinci. An observer of a reproduction of L.H.O.O.Q. in Duchamp’s The Box in a Valise would be inclined to see it as a reproduction of a readymade work of art by Marcel Duchamp. And an observer of Duchamp’s dinner invitation L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved would be inclined to see it as an altered version (made by Marcel Duchamp) of a readymade work of art by Duchamp.

–– ⸪ – –

With respect to the concept agenderism it is relevant to note that Duchamp materialized the same concept with his 1921 readymade called Laundress’ Aprons which consists of two potholders, a photograph of which appears below. One has parts representative of the male sex organ, the other has parts representative of the female sex organ. The potholders materialize agenderism by illustrating that notwithstanding the obvious physical differences that the two objects have, essentially they are the same; because they are essentially the same—they are both essentially oven mitts.

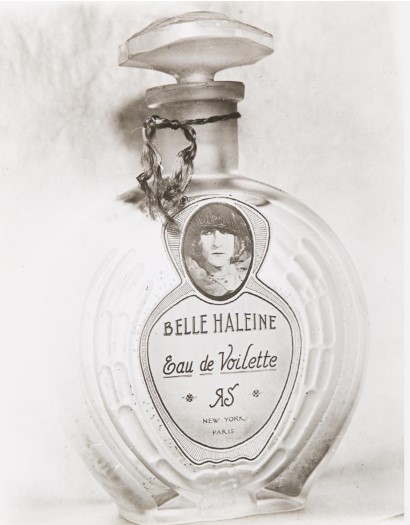

Duchamp also illustrated and materialized agenderism with his 1921 readymade entitled Belle Haleine, which is shown below. It consists of a Rigaud perfume company bottle that Duchamp altered in collaboration with his friend the artist May Ray, who took the photograph that appears on the bottle, of Marcel Duchamp outfitted as Duchamp’s feminine alter ego who Duchamp named Rrose Sélavy. A larger photograph by Man Ray of Duchamp as his alter ego Rrose Sélavy also appears below.

Duchamp’s illustration of his alter ego Rrose Sélavy makes it clear that (irrespective of one’s immutable biological sex), Duchamp was aware that a person’s persona (i.e., one’s gender) is not necessarily, and need not be, entirely or immutably feminine or masculine. Accordingly, a concept regarding agenderism that Duchamp evidenced by means of his display of his alter ego Rrose Sélavy was that one can see a person as being a human being without discrimination or classification by their gender. As is the case with many of Duchamp’s readymades, there are numerous other interesting aspects of this readymade. One of which is that Rrose Sélavy sounds like “Eros c’est la vie”, which is a play on the French phrase that means “Love, that’s life”. Another is that in 2009 the readymade Belle Haleine sold at auction at Christie’s in Paris for $11,500,000.

– – ⸪ – –

A complex readymade created by Duchamp in 1921 that addresses multiple concepts of seeing-as is called Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? It is comprised, among other things, of a birdcage that has numerous small white cubes and a medical thermometer inside, and a cuttlebone protruding through its frame.

The white cubes are commonly “seen-as” sugar cubes; when in fact they are something very different—they are made of marble. Duchamp thereby created this illustration of the concept seeing-as by going so far as to present objects whose material composition, weight and hardness, and their conceivable uses, are all very different from what he knew that they would most likely commonly be seen as.

The juxtaposition of the cuttlebone in the birdcage, and the location of a medical thermometer in a birdcage, were obviously intentionally done, and somewhat boggle the viewer’s mind; possibly to make common things that merely appear out of place cause an observer to be unsure of what they are used for and, therefore, unsure of how to categorize them and what to see-them-as.

– – ⸪ – –

A readymade that Duchamp created to illustrate and make tangible an important philosophical concept regarding seeing-as is his readymade of 1927 called Door, 11 rue Larrey; a photograph of which appears below.

This readymade, constructed with one door, that is hinged to two doorway openings, such that opening one doorway necessarily closes the other, illustrates in tangible form, a concept of seeing-as regarding “duality”. Duchamp thereby illustrated a philosophical concept that antonyms (opposites) entail each other, by materializing the fact that one cannot have the concept “open” unless one necessarily also has the concept “closed”. That is the same concept of duality that is, for example, true with respect to “good” and “bad”; “heavy” and “light’; “hard” and “soft”; “right” and “wrong;” etc. And that, incidentally, relates to the concept of “indifference” which was repeatedly referred to by Duchamp when explaining how he felt about the (already made) objects that he obtained and used in his readymades. What he was saying is that when he selected those objects he did not do so because he saw them as being a member of any particular class or category of objects, or because he saw them as good or bad, beautiful or ugly, or useful for this or for that purpose; but that he did so with “indifference”. And with respect to the word “indifference” it is important to keep in mind that the prefix “in” means “without”. Therefore Duchamp often selected objects for his readymades in a frame of mind that did not see them as anything in particular (he selected them without seeing-them-as being different from or the same as anything else); but saw and selected them as unclassified, previously unidentified, undifferentiated, unnamed things. And that deep, insightful, philosophical concept relating to duality (and, incidentally to not-seeing-as) has been addressed throughout history, in particular by luminaries of Eastern Philosophy.

The ancient (fifth century BCE) Chinese philosopher Lao Tsu, who is credited with founding the philosophical system of Taoism, in his Tao Te Ching (aka, The Classic Book of the Way) says:

When the world knows beauty as beauty, ugliness arises

When it knows good as good, evil arises

Thus being and non-being produce each other

Difficult and easy bring about each other

Long and short reveal each other

High and low support each other

Music and voice harmonize each other

Front and back follow each other

The Third Chinese Chán (Zen) Patriarch, Seng-ts’an, in the following excepts from his sixth century poem Hsin Hsin Ming (a.k.a., Faith in Mind,) which is one of the earliest and most influential Zen writings, states:

Do not hold to dualistic views, avoid such habits carefully.

If there is even a trace of this and that or right and wrong, the mind is lost in confusion.

. . . .

When all things are seen without differentiation,

Your timeless Self-essence is achieved and is One with the Way of the universe

as it is.

No explanations, comparisons or analogies are possible in this causeless,

relationless state.

. . . .

In this world of “Suchness” as It intrinsically is, there is neither self nor other.

To come directly into harmony with such reality, only express non-duality.

When doubt arises say “Not two.”

In this non-duality nothing is separate, nothing is excluded.

The enlightened at all times and places personally enter and realize this Truth.

. . . .

To live this faith in trusting mind of non-duality,

Is to be One with the Way.

– – ⸪ – –

In addition to the foregoing it is important to note that with respect to many of his readymades there are two additional, brilliant but nonetheless underappreciated, aspects of Duchamp’s creativity regarding his readymades.

One is the fact that although the titles that Duchamp often gave to his readymades are cryptic at best, and sometimes incomprehensible or nonsensical, it was appropriate and ingenious for him to intentionally do so—because a title that has no inherent meaning is perfectly appropriate for a readymade that illustrates the fact that objects have no inherent meaning. With respect to Duchamp intentionally doing so, Duchamp’s good friend, the artist Louise Norton, in her 1972 Article “Marcel Duchamp at Play”, when speaking about a readymade that Duchamp gave to her (which she stated she regrets having lost), says that what Duchamp wrote on it was “. . . a designation like all his others, aimed to be as Alice-in-Wonderland nonsensical as possible.”

The second (and possibly even more) ingenious but underappreciated aspect of Duchamp’s readymades relates to the fact that the originals of his readymades were often given away, disposed of, lost or destroyed; and that Duchamp did not consider that to be a problem, and did not have any objection to reproductions or replicas of them (many of which he made himself) standing in place of the original, and being considered of equal importance to the original. And that was so even if the “copy” was merely a photograph of the original, or a replica of it that was made with different materials, or was of a different size, or exhibited in a different manner; and even if the copy was made by someone else. And that was perfectly reasonable and appropriate of Duchamp; in fact it represents a transcendent, deep insight by Duchamp. He recognized that it was the idea, the thought, (that is, the philosophical concept) that is engendered and materialized by the readymade that is important, not merely how, or by whom, or with what materials, it was made, or the manner in which it was displayed; because he understood that the concept, the idea, that was illustrated and materialized by the readymade (which was the primary reason for the creation of the readymade), survives the loss of the original. When Duchamp made reproductions of his readymades (and he did make many) he knew that when the original of a readymade was “lost,” the idea that was illustrated and materialized by the original was illustrated and materialized just as well by its reproductions and replicas.

– – ⸪ – –

When one interprets readymades it is important to be aware that Marcel Duchamp, like countless other great artists, did little or nothing to publicly explain why he made what he did, what they mean, or (especially in the case of Duchamp) the philosophical concepts that he intended to and did illustrate and materialize with his Art. That is certainly so with respect to Duchamp’s readymades; because he believed that the “meaning” of a work of Art often cannot adequately be put into words. Duchamp has often been quoted (although the source of the statement is not definitively known), as having said: “As soon as we start putting our thoughts into words and sentences everything gets distorted, language is just no damn good—I use it because I have to, but I don’t put any trust in it. We never understand each other.”

Duchamp’s belief that words are inadequate to effectively convey one’s thoughts is neither unique nor strange. It has been stated by numerous enlightened individuals throughout history; for example:

The nineteenth century philosopher Thomas Henry Huxley (1825 – 1895) said:

A world of fact lies outside and beyond the world of words.

The Indian philosopher Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, aka Osho (1931- 1950) stated:

Enlightenment, true understanding, cannot be conveyed by words. The keys to wisdom cannot be delivered through the mind by words or understood by conscious thought; whatever is said about it will be misunderstood. Only some hints, some indications, some gestures can be communicated by words.

In the sixth century, Seng-ts’an, the Third Patriarch of Zen stated:

Words! Words!

The Way is beyond language.

Words never could, cannot now, and never will describe the Way.

More than two thousand years ago the Roman poet Ovid (43 BCE – 17 CE) said:

There is nothing in words; believe what is before your eyes.

Duchamp also did not explain his Art both because he thought that the creative act was to some extent intuitive, and because he realized that what a work of Art means to the artist will often differ from the meaning that someone else who views it will have. Duchamp was well aware that a viewer’s personal, pre-existing knowledge, opinions, feelings, preferences and world-view will play a large part in determining how a viewer judges and interprets a work of Art (that is, what the viewer will think about the work of Art, and see-it-as.)

In Duchamp’s BBC TV live interview in 1966 he stated: “I cannot explain everything I do, because I do things why people do things, and don’t know why they do it.”

In Duchamp’s lecture The Creative Act which he delivered at a convention of the American Federation of Arts in Houston, Texas, in April 1957, he said:

Let us consider two important factors, the two poles of the creation of Art; the Artist on one hand, and on the other the spectator who later becomes the posterity.

To all appearances the Artist acts like a mediumistic being who from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing. If we give the attributes of a medium to the Artist, we must then deny him the state of consciousness on the esthetic plane about what he is doing or why he is doing it. All his decisions in the Artistic execution of the work rest with pure intuition and cannot be translated into a self-analysis, spoken or written, or even thought out.

‧ ‧ ‧ ‧

In the last analysis, the Artist may shout from all the rooftops that he is a genius; he will have to wait for the verdict of the spectator in order that his declarations take a social value and that, finally, posterity includes him in the primers of Art History.

I know that this statement will not meet with the approval of many Artists who refuse this mediumistic role and insist on the validity of their awareness in the creative act—yet, Art history has consistently decided upon the virtues of a work of Art through considerations divorced from the rationalized explanations of the Artist.

‧ ‧ ‧ ‧

All in all, the creative act is not performed by the Artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act. This becomes even more obvious when posterity gives its final verdict and sometimes rehabilitates forgotten Artists.

In Marcel Duchamp’s letter of August 17, 1952 to his sister Suzanne Duchamp and her husband, the Artist Jean Crotti, he stated: “. . . there does not exist a painter who knows himself or knows what he is doing . . . .” Nonetheless, there is nothing more certain than when an artist does create a work of Art there is something that such artist definitely desires and intends to create, whether the artist understands or can articulate it or not, and whether or not the artist’s motives were conscious or unconscious. When an artist makes a work of Art, it is not entirely an accident that the artist made that particular thing.

With respect to the foregoing it is important to understand the implicit distinction regarding “Art” that Duchamp makes in his article “The Creative Act” between those things that someone creates that do constitute, and those that do not constitute, works of Fine Art. He said:

But before we go further, I want to clarify our understanding of the word “Art”—to be sure, without an attempt to a definition.

What I have in mind is that Art may be bad, good or indifferent, but whatever adjective is used we must call it Art, and bad Art is still Art in the same way as a bad emotion is still an emotion.

Unfortunately, one consequence of the philosophic, conceptual, and often recondite and esoteric nature of Duchamp’s readymades (as well as a result of his cryptic statements about, and his reticence to publicly explain, his Art) is that that has led more than a few individuals to assert the preposterous proposition that something is Art (with a capital A, as if it is good, great, or what may best be called “Fine Art”), just because some person had the idea to select and/or make (by just about any means), and/or exhibit (in some way), something or other (just about anything), regardless of whether by doing so that person has or has not demonstrated any exceptionably good and fine abilities or achievements. The unfortunate consequence of which silliness is that all sorts of things made by amateurs and beginners as arts and crafts, and a considerable amount of crap that people select, make and exhibit, although it may be their “Art”, is too often accepted by others as if it were Fine Art, and as if its maker and/or exhibitor is an artist who has created a work of Fine Art. All of which silliness has merely contributed to a great many people foolishly dispensing with and disparaging exceptionalism and a meritocracy.

– – ⸪ – –

There are some individuals who have said that Duchamp was not being serious but merely joking when he created readymades. Although Duchamp certainly saw and created humorous aspects in some of his readymades, he was nonetheless essentially, exceptionally serious about his Art. Duchamp’s friend Louise Norton, in her Article in The Blind Man, stated regarding Duchamp’s readymade Fountain: “. . . there are those who anxiously ask, ‘Is he serious or is he joking?’ Perhaps he is both!”

In any event, the following quotation by the English writer, philosopher and Art critic John Ruskin in his book Modern Painters (published in 1843) may best encapsulate the essence of what justifies Macel Duchamp’s reputation as a luminary in the world of Fine Art: “He is the greatest Artist who has embodied, in the sum of his works, the greatest number of the greatest ideas.” [Emphasis added, Ed.]

John Ruskin, with the following statement in his book Modern Painters may have also best articulated a reason why many individuals misinterpret or disparage Duchamp’s readymades, and fail to appreciate their nature and scope as great works of Fine Art:

The highest Art, being based on sensations of peculiar minds, sensations occurring to them only at particular times, and to a plurality of mankind perhaps never, and being expressive of thoughts which could only rise out of a mass of the most extended knowledge, and of dispositions modified in a thousand ways by peculiarity of intellect – can only be met and understood by persons having some sort of sympathy with the high and solitary minds which produce it – sympathy only to be felt by minds in some degree high and solitary themselves.

Incidentally, it bears mentioning that it is not unlikely that some highly intelligent, knowledgeable Art experts do in fact know that Marcel Duchamp’s readymades were created to, and do, illustrate and materialized philosophical concepts, and understand how they do so; but have kept that knowledge private, shared only among themselves, and not with the public. Some reasons why that may be the case, are described in the following quotations:

Any effort in philosophy to make the obscure obvious is likelyto be unappealing,

for the penalty for failure is confusion

while the reward of success is banality.

An answer, once found, is dull,

and the only remaining interest lies in a further effort

to render equally dull what is still obscure enough to be interesting.

Nelson Goodman (1906 – 1998)

And since it is not unlikely that banality would often be the result of Art “experts” making their private knowledge regarding Marcel Duchamp public, they may be motivated to keep it secret among themselves because they realize that it would be a disservice to the Art world to trivialize achievements as brilliant as those achieved by Marcel Duchamp with his readymades and other works of Fine Art.

Another reason that some experts may keep their knowledge regarding Duchamp and his Art private may be because of an awareness that:

Whoever sets out to persuade men to accept a new idea, or one which seems to be new, not just as an idea, but as a truth that is felt, should know beforehand that the human mind is not a blank sheet, on which one can write with ease, and should not therefore grieve or despair when he finds that people do not pay attention to him.

Ahad Ha’am (1856 – 1927)

– – ⸪ – –

All told: This essay has endeavored to establish that Marcel Duchamp materialized philosophy; by materializing with his Art philosophical concepts that highly insightful individuals throughout history have developed to understand and explain how people think about the objects that we see—which concepts we have generally categorized as “seeing-as”. In the light of the many instances and ways in which Duchamp’s readymades materialize philosophical concepts, and when that is considered together with the statements made by Duchamp, by his friends, and by the other artists, philosophers and luminaries throughout history that are quoted above, it is hoped that this endeavor will be found by some to have in fact established that Duchamp created readymades to materialize, and did materialize, philosophical concepts regarding how we think about the objects that we see.

Nonetheless, one would do well to be aware that as Elaine Lobl Konigsburg illustrated in her 1967 book From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, no amount of evidence is sufficient to convince some individuals of the truth of facts relating to a work of Fine Art.

Be that as it may, it is safe to say that Marcel Duchamp and his readymades have passed what may well be the most critical test for determining the importance of works of Fine Art: They have “stood the test of time”. For more than a century Marcel Duchamp’s readymades have been recognized world-wide as ground-breaking, highly creative works of Fine Art. From the early twentieth century to date, Marcel Duchamp has been widely recognized as a luminary in the world of Fine Art, and one of the most ingenious and influential artists of the twentieth century. During his lifetime and to the present, Marcel Duchamp, his Art overall, and his readymades in particular, have been recognized as great artistic achievements, and discussed at length in innumerable books, articles, art classes, seminars, video presentations, and conferences. Readymades have been, and continue to be, prominently exhibited in the permanent collections of museums throughout the world. Entire rooms in some of the most highly regarded museums of Fine Art (including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Philadelphia Museum of Art) have been devoted to the display of readymades and other works of Art by Marcel Duchamp. During his lifetime Duchamp was a leading figure among avant-garde artists in France and the United States. Among Duchamp’s friends who held him in the highest regard, were Constantin Brancusi, Man Ray, Diane Arbus, Alfred Stieglitz, Mary Reynolds, Francis Picabia, Andy Warhol, Beatrice Wood, John Cage, and André Breton. That is what bears testament to the prominence, great achievement, and creativity, of Marcel Duchamp and his readymades in the world of Fine Art.

. . .

.

— —